|

|

||||||||

MRS. THATCHER'S WAR A REVIEW OF SHRAPNEL GAMES' THE FALKLANDS WAR: 1982

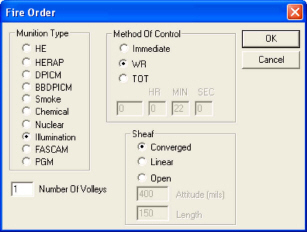

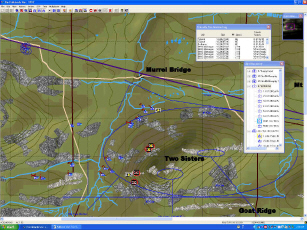

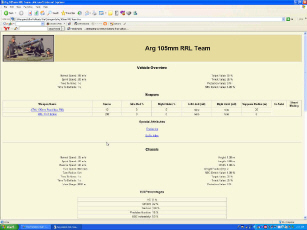

The Falklands War was one that one side bet would never happen. The generals who ran Argentina were losing whatever support they had been able to beat out of their country, a situation aggravated by a stumbling economy. Giving up power was hardly an option the junta, so it played the nationalism card, specifically las Islas Malvinas, known to most of the rest of the world as the Falklands. Two nations had a claim to the islands. Argentina's was by right of discovery, which was by Spain but inherited by Argentina. Great Britain's was by right of occupation; the Falklands were a British possession, long inhabited by British population, albeit a small one. Under international law, both claims were valid. In practice, that of the United Kingdom was the stronger one, under the time-honored principle that possession is nine-tenths of the law. Britain had possession, secured by a small force of Royal Marines. President General Leopoldo Galtieri and his associates were emboldened by some of Britain's own policies. One was to reduce Falkland Islanders' level of citizenship to a level closer to that of Hong Kong's inhabitants. The other was a cost-savings move, the withdrawal of the Royal Navy's only vessel in South Atlantic waters, the ice survey ship Endurance. Neither was intended as a signal to Buenos Aires that the United Kingdom was losing its commitment to keeping the Falklands. But that was how they were interpreted by the junta. So on 2 April 1982, the Argentines launched Operation Rosario. Not really a battle, it was more of a coup de main that ended in the surrender of the garrison. With that the Falklands become the Malvinas. It was now Argentina's turn to miscalculate. The generals calculated that they would reap a reward of nationalistic fervor easily translated into legitimacy for their own regime. They got it in full, at least in the short term. They also counted on Britain accepting the fait accompli and not responding in a material way. They counted wrong. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was not about to accept either an insult or aggression, and the seizure of the islands certainly met the criteria for both. At her direction Britain's military, after decades of economizing a shadow of its World War II self, assembled a task force to retake the Falklands. It was built around two aircraft carriers, the modern Invincible and the older Hermes, not far from sale to India, with a reinforced brigade of Royal Marines and the army's Parachute Regiment, two of the United Kingdom's true fighting elites, supported by elements of the Royal Air Force. Later another brigade would arrive, built around the Welsh and Scots Guards and Gurkhas. Just getting to the South Atlantic would be a struggle. At one time Britain could have sent a mighty fleet using a string of colonial possessions for bases and logistical centers. In 1982 the task force consisted of every warship capable of making the trip, and was still small, and there was just one major base along the way, Ascension Island. Then there was the actual war. Argentine pilots from both the air force and the navy owed nothing to anyone for bravery, and accumulated a list of sunken and British vessels to prove it. On shore, Argentina's garrison of conscripts and second-line units were equipped just as well as their foemen and, in some categories of winter clothing and small arms, better. In the end the superior training, cohesion, and persistence in the face of danger demonstrated by the British soldiers and Marines carried the day. That and the fact that they confounded Argentine expectations by making the trip in the first place. Ultimately the consequences of the British victory rippled to both countries and beyond. The Argentine military's failure was a major, even deciding, factor in its fall from power. The years of dictatorship and torture gave way to the restoration of democracy. On the other side of the Atlantic, Britain showed that after its own long decline in power and Empire, the lion still had teeth and the resolve to use them. There were some misleading images in the wake of war. Many were of dazed and confused Argentine soldiers marching into surrender. Together with the enduring phenomenon of the victors writing the histories, especially to an English-speaking audience, one could get the impression that the soldiers and Marines had an easy time beating up on mobs of pitiable boys who did not want to be there. There are more than a few British veterans who would beg to differ. Their war was far from easy, as violent and savage as any infantryman's personal war could be. With their helicopter transport largely destroyed by an enemy strike on the ship bearing it, the groundpounders ended up pounding ground, from San Carlos water to the capital of Stanley on the other side of East Falkland Island, on inferior footwear and in substandard cold weather gear. When they had to fight, they won, but not against an enemy just waiting to cut and run or surrender at first sight. They fought, and sometimes with a lot of determination. The Falklands War: 1982 has a history of its own. Derived from Shrapnel Games' successful ATF: Armored Task Force game, it marks a major change in the system's focus. ATF and last year's Raging Tiger, addressing future modern combat in Korea, are hypothetical. The Falklands War: 1982 changes the focus, and for the first time simulates an historical conflict. According to the game's documentation and Shrapnel's web site, it will not be the last. CONFLICT IN REAL TIMEBy definition The Falklands War: 1982 is a game of strategy that takes place in real time, but to call it a real-time strategy game would be a dreadful mistake. It is of a completely different genre than Rise of Nations or the venerable Starcraft, or with any other game of exploration/resource exploitation/technology and production for that matter, as they share nothing more than playing against a clock instead of a turn-based structure. Whereas the mainstream of the RTS genre is fantasy, even when it generates an deceptive historical milieu, The Falklands War: 1982 aims for simulation, and achieves it to an admirable extent.. Unfortunately the first page of the manual makes just such a comparison, as does the introduction to Raging Tiger. The closest relative of which most players should be familiar is the Harpoon series, so all conventional real-time strategy games are fundamentally irrelevant as points of reference. A player has to think more like a commander than he does in most other games. There is the pressure of time, a need to allocate combat resources, and above all to plan. The player has to deploy his troops, then plot out avenues of advance, missions, and preparatory artillery fires. Then once the battle starts, he intervenes to exploit success or mitigate failure, coordinating more artillery, air and naval support. In some scenarios too he has extra tasks of managing transportation and resupply. It certainly is a different animal than what most gamers associate with RTS. The system permits one of the computer wargaming's most extensive ranges of scale and perspective. As the equivalent of a battalion or brigade commander in most battles, he can give orders to companies, the highest and for the most part the most appropriate units, trusting junior officers played by the artificial intelligence to carry out tasks. It also happens to be the easiest level to command, and many will enjoy the game the most if they keep this most general of viewpoints. There are two other levels below companies, and the player can give direct orders to platoons and, below them, individual vehicles and fire teams. This is where the system can become extremely interesting, as the player can fine tune his strategies. Commanding one vehicle or a couple of soldiers is quite taxing for a battalion commander, which is a big reason why armies leave the jobs of junior officers and sergeants to junior officers and sergeants. Yet there are times when a leader requires to see things at a much lower level than his own usual one, and also to intervene. The ATF system allows this and encourages it. The truth is that nothing should be totally below the player's attention. Looking at a battalion's worth of tanks and fire teams is a quick trip to sensory overload and confusion. Looking at platoons more frequently lends a commonly needed degree of granuality to his perspective, with occasional reversion to companies to give general orders, and to the tracks and grunts to see how and why things are going right, catching opportunities as they are born, or seeing the start of a crisis and the consequent call to intervene. A good commander knows when to get out of Dodge City, and the best way to the edge of town. Looking to the lowest level of command can be instrumental in letting him know when to implement those contingency plans to get out of Dodge. Then there is the issue of fire support. Artillery is one of the key prerequisites to winning, and it is the part of the game that is always treated in great detail. The player assigns missions to batteries, or even individual guns, chooses a target, a pattern, and the ammunition type. Finally, he chooses between delivering the mission immediately (a good choice when the alternative is overrun), when the firing unit is ready, or a "time on target" mission. In the last, the shells or rockets are directed to land at a specific time of the player's choosing. This is the most predictable and, should several units have their shots synchronized, overwhelming. My own experience with the series prior to The Falklands War: 1982 was with Raging Tiger, which I found to be a game both demanding and absorbing. It has an unusually steep learning curve, even without looking down to what the sergeants do, and it took a lot of work to get a grip on the interface and how to get the most out of it for the task at hand. That means accelerating the passage of time through those long periods of tedium that typify one part of a soldier's life, then pushing in the temporal throttle for the others: Moments of terror, crisis and decision. It also means knowing the appropriate times to issue orders to the different levels of units, assigning them the right formations, and generally figuring out how to tell the game what to do. All of that is on top of having an idea of what to do in the first place. It calls for a great deal of time and attention. Ultimately though it is rewarded handsomely, at least in my experience, with a greater appreciation and respect for what it takes to make life and death decisions on the modern mechanized battlefield, admittedly without that inconvenient factor of real danger and death. As portrayed in Raging Tiger, a professional soldier's life is not for the stupid any more than it is for the weak and timid. There is one

element missing from that game though: History. Not so with The

Falklands War: 1982, as it adds another element of reality. This is

a real war war, examined and analyzing exhaustively in the last twenty-three

years. Players have the chance to learn its chronology, the course of

events, and how it ended with a British victory. There is no hiding

behind speculation here. A LENS FOR REALITYPlacing real battles into the context of this game calls for more changes to the player's way of going about things than it does for the game system itself. That speaks volumes for the essential soundness of the game engine, as history can punch a giant hole in even the best-informed and acutely analyzed hypothesizing. The Falklands War: 1982 survives the reality test unscathed. As with Raging Tiger, it fosters renewed appreciation for those who were able to accomplish their missions in the war, in particular attacks that not only took the objective but did so without extreme casualties. The first change that players are likely to notice concerns deployment. In Raging Tiger, a human player had rather wide latitude how and where to set up units, even static defenses such as improved defenses and minefields. That was one of the game's major challenges in fact. The Falklands War: 1982 dispenses with it. The game's setup depends on the historical situation at the start of the battle, not the player's wishes. In one way it makes the game a little easier, calling upon historical commanders to set the guidelines. This continues into the conduct of the battle itself. The scenario background is extremely detailed and lucid so that a player has a valid example of play, again helpfully provided by Argentina and the United Kingdom. This is just the first sort of guidance. Each scenario also comes with an operational order (OPORD) from a higher-level headquarters that lays out the objectives and, a big reason why it should be read carefully, an intelligence estimate of the other sides' units and positions. Finally, the maps continue its predecessors' practice of laying out the start lines, unit boundaries, and objectives. Collectively, they amount to a constant reminder of historical courses of action, without having to call up a separate window. A player can play the game his own way of course, and as usual that is much of the fun of the game. But it is good to have a guide of what the historical actors did first. Beneath these overlays, the game maps are things of beauty and detail, particularly when one chooses the map option combining color with contour lines. There is one unusual and counterintuitive prerequisite for this though; in The Falklands War: 1982, like Raging Tiger, the best graphics are possible only with 24-bit or lower color resolution. In practice, with a computer within a couple of years of being state of the art, this demands that the user actually turn his screen graphics back. Once done, the results are impressive. The popular image of the Falklands might be of wind-swept, bland islands, dominated by a few modest hills and mountains, important for solely military reasons. There is one real town, Port Stanley, and a bunch of little settlements with a few buildings, maybe a grass airstrip. In short, it looks just like the kind of bleak, treeless place that makes the color green look bad, and where it is only natural that sheep should outnumber the people. As happened historically, the majority of the action takes place on East Falkland, and The Falklands War: 1982 offers a more sophisticated look at the place. It does show the extremely low population density, and settlements really do look like the back end of nowhere. The are no paved streets or roads outside of Port Stanley and its environs, and precious few unpaved tracks for that matter. Yet it is not a featureless place by any means. Contours are the prime determinants of lines of sight, and a player absolutely has to understand them closely to get the most out of his longer-ranged direct fire weapons, such as heavy machineguns, or to hide from the enemy's. In the same vein, the rise and fall of the land is most pronounced around the peaks toward the center and east of East Falkland, but one ignores the lesser slopes only at one's own risk. There are long fence lines, a feature seldom encountered in a modern grand tactical game. These further mark the boundaries of the different properties and sheep stations, which are named. Additionally, the game maps accurate show that this is a wet place. East Falkland has many streams that, in isolation, are hardly worth noting. Collectively though, they are something more. Likewise, the island has many small ponds and lakes, another indication of just a soggy place it is. From a military viewpoint, they channelize movement for the benefit of the defenders even more than the streams. The game shows rocky outcrops, often but not always atop heights, and beaches. Far from being an undistinguished soggy mess broken by some peaks, the battlefields of The Falklands War:1982 are actually rather interesting places. The most compelling aspect of the maps has nothing to do with obstacles, objectives or lines of advance. It is simple reality. This is a real place, where the streets do have names, and so do the villages, ponds and sheep stations. It is much more compelling to fight over Mt. Longdon or Goose Green than it is to do so over a couple of places identified only by map grid. A KNIFE FIGHT IN THE DARK, WITH BIG GUNS BEHINDThe Falklands war was one for the infantry. Heavy armor did not appear, in large part because the wet ground provided poor footing for tanks. British Chieftains and Argentine Shermans are in the order of battle, but only for purely hypothetical scenarios. Some of the hypothetical battles are based around believable variables, a unit deployed differently or a counterattack not made historically. However, the ones involving tanks are founded on the proposition that the islands had firmer and drier ground, a proposition that defines geography and geology instead of human decisions. Barring this substantial suspension of belief, The Falklands War: 1982 portrays an infantryman's war. The poor bloody infantry does the fighting, backed by artillery and more distant support from airpower and naval gunfire. In the end, it is always the PBI that does the heavy lifting for both sides. Additionally, it is almost never by the light of day. The long nights of fall deep in the Southern Hemisphere make darkness the natural state of affairs, when battles are fought instead of rest, healing and maintenance. The poor visibility combines with the primacy of the infantrymen, and the weapons he can carry, to make combat take place at much shorter ranges than it can in Raging Tiger. It is war up close and personal. There is a new choice to be made that has a powerful effect on whether the foot soldiers do their job. The Falklands War: 1982 demands that players set the quality of the forces on both sides, with three options: Green, Veteran and Elite. In most cases I set the British at Elite, due to the exceptional esprit de corps and high standards of the Paras, Marines and Gurkhas, to which can be added their extensive training in light infantry operations. The SAS on Pebble Island is always elite, and I wish that there was a higher rating for them. For the Guardsman of 5 Brigade, Veteran is probably the best choice, not because they were inferior, but because their training was more for the mechanized battlefield of the North German Plain than the hills of East Falkland. I gave a lot of thought to the skill level of the Argentines. Their army was not entirely an unmotivated mob with officers better at killing suspected dissidents than fighting a real army. At times they performed bravely and effectively, though seldom with the nearly insane personal bravery of their comrades in the air. However, in the end I nearly always choose Green, to replicate the differential in unit quality between Argentine and Briton (and Gurkha). Even green units can do a lot of damage when charged by the best that the British armed forces can offer, so a blind charge at even badly outnumbered Argentines is going to prove Roy Geiger, USMC's advice to Chesty Puller at Pelelieu: "You can't take that hill with dead Marines." Without care, planning, preparation, and coordination, a British attack anywhere in the Falklands is going to look more like the Charge of the Light Brigade than any of the historical outcomes. It would be easy to say that offensive operations, and these are mainly the domain of the British, require a lot of artillery preparation and support fire by the battalions' heavy weapons units, particularly mortars and heavy machineguns. That is half the problem though, and is worthless without understanding the other half. That is coordination. A player has to have his units attack together and not piecemeal. More than a statement of the lethally obvious, it is one of those tasks easier to say than to do in most cases. Different companies will move to their start lines at different rates, and then tend to do the exact same thing on their way to the enemy. Moving one in advance of another permits the defenders to concentrate their fire and defeat them in detail. Additionally, the support fires have to be coordinated skillfully and with the best timing possible. As the game manual states, it is better to plaster one small position with all the firepower that can be mustered, all at once, then move to another, instead of spreading this precious resource from the beginning. The principle of mass is easily discerned in The Falklands War: 1982. The player, regardless of nationality or being on the offense or defense, has to keep an eye on artillery ammunition too. There are no points for saving it to the end of the game, no reward for economizing, so it should be used freely. Just not stupidly; do not continue to bombard foxholes, for example, if the occupants are already dead. Save it for introducing the other sides' living soldiers to the Almighty rather than abusing corpses. Running out of ammunition at the wrong time is one of the worst events anytime, for anyone, in the game. When the infantry are taking a beating from their enemy counterparts, and finding that the fire mission on which they depend is not coming, that can be fatal. Furthermore, artillery is not something to be used to wipe out the enemy so that the infantry has no harder mission than stepping over the carnage to reach their objectives. Again, coordination between arms is key. Soften up the enemy positions with liberally, but intelligently, applied firepower. That should not be confined to artillery; heavy weapons units, ships at sea, airpower, these can get the best results when combined. Mass firepower. Include the attacking rifle units too. An "Attack by Fire" mission is quite useful for this purpose. Also, do not limit the fire to high explosive. The Falklands War: 1982 does not have the plethora of advanced and specialized ammo present in Raging Tiger; there is high explosive, smoke and illumination and nothing else. On a battlefield without tanks, that can be enough though. With battles taking place at night, illumination rounds are crucial, especially as this war lacked the abundance of night vision equipment that the United States has used in Iraq in its most recent conflict. Do not fire repeated volleys of them by a massed battery; one flare fired by one gun is generally good enough for one place. Use the other guns to spread the light elsewhere if need be. One should take care too that only the enemy is illuminated. In this environment being seen is a frequent prelude to being dead, so do not do the enemy a favor by lighting one's own troops. Fire them a little behind the enemy lines, or suspected lines, so that they are lit up and the attackers are not. One might also see more enemy troops hiding in the rear, eliminating a nasty surprise before it can happen. The final advice for artillery is to not give the other side a chance to recover. When the defenses appear attrited, give the infantry companies assault missions. Send them forward in close coordination with the artillery, though not so close that short rounds kill one's own soldiers. Give the infantry a local correlation of forces that permits them to use the bayonet and grenade to carry the position. No, this is not an easy game to play well. I have the casualties to prove it. Players will find that it takes longer for events to develop than in many other games, especially turn-based ones. There is little instant gratification. So patience is a virtue in the Falklands, one infinitely better than a rash charge into the enemy guns. That can amount to a weakness in the game as well as one more example of realism. There are times when 8x time compression is not fast enough, starting with Operation Rosario. After the Argentine special forces land near Stanley in advance of the main landing force, there is a period of maneuver devoid of combat that can last six hours. As the Argentine player, I can attest that it can be about as fun as watching paint dry. CONCLUSIONSThe Falklands War: 1982 is not for the faint of heart, or gamers looking for escapism and entertainment ahead of daunting historical challenges. The ATF engine requires a greater commitment and investment in energy to learn than any other I can recall. In my case, I was able to get into this game fairly quickly and learn its distinguishing marks in relatively short order for one reason: I had already spent weeks, months in fact, playing Raging Tiger. I was able to transition to the infantry-oriented battles in the South Atlantic from mechanized combat in Korea, an easier task than assimilating the system in the first place. I know, because I did both. Due to this complexity in system and strategy, the manual takes on a higher importance, and even the most confident players will find theirs dog-eared during the learning stage. This documentation is pretty good at what it aims to accomplish, starting with a tutorial on the SAS's Pebble Island raid, followed by a comprehensive rundown of the controls and menus, ending with the expected advice on strategy, scenario notes, and data on selected equipment fielded by Britain and Argentina. It could be better though. Some of the explanations are little too brief to be effective; the description of how to resupply units comes to mind first. On at least one occasion, The Falklands War: 1982 preserves a shortcoming from the Raging Tiger book and online help files. When placing obstacles in the Korea game and placing linear patterns of artillery fire in both, their orientation is determined in mils. This is all well and good, but few players are going to grasp that unit of measurement on their first try. It would be a big improvement in future installments to present a clear and easily-found definition of mils, preferable in relation to degrees on a compass. More than anything though, this manual needs an index. Despite the occasional gap, it is both crucial and usually effective for learning and reference. However, it would be much better for the latter if there was a comprehensive index. For all this though, The Falklands War: 1982 remains an extremely impressive product. One of the highest forms of praise that one can offer a wargame, on computer or cardboard, is to say that it makes sense. This one makes sense, a lot of sense at that. The only counterintuitive element is the desirability to reduce the monitor's color resolution. Everything else, the mechanics, the strategies, the performance and interaction of the units, works in an historical, realistic, and easily-discerned manner. The detail in its order of battle is as impressive as the detail of its maps. It is easy to find out outside the game the British order of battle at battalion/commando level. The Falklands War: 1982 goes much deeper and broader than that. It looks into the structure of those units, and the specifics of the secretive 22 SAS Regiment too. With a portrayal of units down to fire teams, the game's detail is astonishing, and put to good use. It does not shortchange Argentina either. These are not generic "Argies," but forces every bit as identifiable, though neither famous or effective, as the British. One can see this clearly in the first scenario, their invasion of East Falkland, with a detailed assortment of army and marine units, led to the beaches by naval special forces analogous to the US Navy's SEAL's, the Royal Marines' Special Boat Squadron. It would be news to a lot players, even the ones with the better knowledge of the Falklands War, to know that the oft-maligned Argentine military possessed such elite units. It certainly was to me. Ultimately, The Falklands War: 1982 is a game for the hardcore historical gamer. It demands a great deal and assumes that the player brings to it a grasp of military concepts and practice substantially above that of the casual, purely recreational player. This is a simulation far more than a game. It is also an education. As with most educations, the rewards are directly proportional to the effort invested. Plus, it just makes sense.

|