|

|

||||||||

íVIVA EL PRESIDENTE! FUN WITH ECONOMICS AND GOVERNMENT IN TROPICO

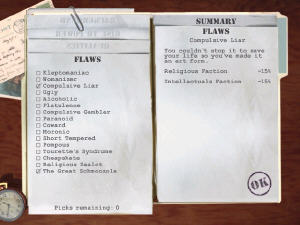

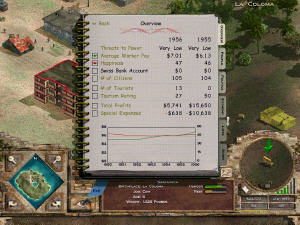

Simulations do not have to simulate war. It seems obvious, but from the computer gaming habits of many wargamers, one would never know it. Tropico is a simulation from Pop-Top Software that puts the player in charge of a backwater Spanish-speaking island in the Caribbean. The flyspeck nation starts with little more than a limited amount of land, a small population that lives in shacks, a presidential palace, and the aspirations of its president, who happens to be the player. Designed with tongue decidedly in cheek, it touches on every available banana republic stereotype, in a way that is a lot more fun than offensive. The game was first released in 2000, followed by a Paradise Island expansion, and then in 2002 in a Mucho Macho edition combining both. After eight years, Tropico's combination of economics, real-time strategy and silliness remains addictive. Unlike most real-time strategy [RTS] games, war and conflict are not central elements to play in Tropico, and are to be avoided. There is no chance of invasion anyway, as there are no foreign enemies; any armed enemies are going to be of the domestic variety, either rebels disgusted with the player's rule, or a military establishment unhappy that its own goals for power and wealth are not being met. The first conducts insurgency that requires an army to fight, and in the second, loyalist factions defend the regime against coup attempts. In either case, there is a fundamental principle that a player has to remember at all times: Success depends on one's relationship with the island's people. Winning and losing both start at home. Making money is vital to game play. As in most RTS games, one gets it through resource exploitation, starting with farming. Farms produce corn, important to keeping the people fed, or a succession of cash crops, which fill the coffers instead of the bellies. Mining also yields revenues, and fishing is a good way to feed the population and play to an export market. In time the player might also try to build an industrial base. But Tropico is Tropico, not the Ruhr or Monongahela Valleys, and trying to make the island an industrial powerhouse is not generally a good idea. Then again, the factories available for construction are the kind to be encountered in Cuba or the Dominican Republic than Essen or Homestead: Cigar factories, fish canneries, and rum distilleries, not steel mills or coke ovens. In most games, tourism is a driving engine of economic development. One builds hotels to lodge foreign visitors, and attractions to keep them happy and increasingly separated from their money. Hotels come in three varieties, from the cheap to the luxury, plus beachfront bungalows and villas. Tourist attractions often start with beach attractions and scenic overlooks. From there, the player can move up to swimming pools, nature preserves, and miniature golf courses, then casinos and nightclubs. It is not just important to attract tourists; La Republica de Tropico requires that they be of the right sort. The first foreigners to visit the island are most likely to be the aptly-named "slob tourists," who tend to be grossly overweight, ugly, badly dressed and, most crucial, lacking in disposable income. Spring break visitors are likewise light in the wallet, but look a lot better on the beach. Both, especially the slobs, are looking for a cheap vacation, regardless of whatever else the island might have to offer. To attract the better class of people, one needs better lodgings and attractions. All the rich yanquis and Europeans in the world will not be of any value though if the people are not served. The player has to make life better, satisfying and fun for the natives. Secondarily, there will be a lot of jobs that the locals either cannot or will not do, particularly in the hospitality industries and those requiring a modicum of education. Immigrants thus become important to the economy, so attracting them to the island becomes a means toward victory. People are happier when you give them money. At the same time, raising wages too high and too fast cuts into the profits. Housing is a basic need, and an island in which everyone lives in a hooch is not going to satisfy very many for very long. In addition, people in corrugated tin shacks do not pay rent, so better housing can mean more money in the regime's pocket from people happy to pay it. Similarly, there is a need for education. Forget the personal enrichment; there are some jobs that require a better-trained worker, and attracting foreign guestworkers can be extremely expensive. Thus the gamer has to build a high school sooner rather than later, and if he can, a university. Illiterates are as common as coffee on Tropico. Smarter people are a much more precious commodity. High-school graduates comprise the industrial workforce, teachers, police, army and priesthood, and college graduates are the doctors, engineers, intelligentsia and prelates of the country. There is a need for healthcare, and that is always provided by the state. The more subjective needs of the people need to be addressed as well. They need to be entertained, and that calls for pubs and restaurants, both of which generate profits. There is a need for religion too, calling for a church and possibly a cathedral. As in the real world, they are not mutually exclusive. One finds priests hanging out in the cabarets, and the showgirls they ogle going to Mass on Sundays. Both people and things require protection. Soldiers are necessary to guard the palace and protect against rebellion and coups, so guard stations, armories (where college-educated generals are trained), and perhaps a large army base are in order. There is also the danger of crime, and to keep that in check one needs cops and police stations. The human scale of Tropico is that of the individual. Each person on the island, from infants to the elderly and including the native-born, immigrants, and tourists, is treated as an individual, with his or her own background, needs, attitudes and allegiances. Keeping the populace as whole happy, and maintaining their respect, is a key to staying in power. There is also an element of party politics too, as individuals support various ideological factions. There are capitalists, Communists, a religious faction, and even environmentalists, all with their own agendas. Communists, for example, are more likely to demand quality housing, and the intellectuals will want schools. Capitalists see the future as being built in factories, or gained through developing tourism, and environmentalists want a clean island. Everybody wants something, and not everyone can be satisfied, so the player has to look at the size of the factions and try to placate the ones that matter more. When a small Communist faction is crying out for better housing, for instance, and a large religious party wants a church, the church gets built first. The dichotomy of dictatorship and democracy enter the equation, and the player can rule as a crooked despot or govern as an honest apostle of democracy, or perhaps something in between. Periodically, the people will call for elections, and most frequently it is a good idea to call them. Whether they are honest elections is another story, though fixing the vote count always results in a loss of respect, sometimes in frustrated democratic aspirations, and if the player has alienated enough of the people, fails to relect the regime altogether. A player can use the tools of repression too. Troublesome individuals can be bumped off or thrown in jail, if one has bothered to build a jail, and it is possible to declare martial law. One can even revert to the bad habits of the Inquisition, persecuting heretics and staging a "book barbeque." Just as distasteful, a player can institute Prohibition against live-giving booze. El Presidente is just like any the people in that he or she has a personality, based on many variables, and based loosely on a real-life or fictional model. The list of role models starts with Che Guevara and Fidel Castro, and includes such Latin, if not Caribbean, luminaries as both Juan and Evita Peron, Violetta Chamorro, Papa Doc Duvalier, and Raphael Truijillo. There are some positive aspects to every type of leader. A Fidel Castro will appeal more to the Communists, and maintain a better relationship with Russia. Violetta Chamorro is incorruptible, and a democrat, generally good for business. Other variables are not so possible. A president can be "ugly as sin," paranoid, an alcoholic, a cheapskate, a compulsive gambler, or a complete moron. Sometimes a pretty good ruler has one or more of these flaws, making good government possible but complicated. For example, a generalissimo will have a way with the soldiers, but if he is a certified moron, there is no way that the player will ever build a university. There is one thing that many Tropican presidents can be: A crook. There are opportunities for graft and corruption, most notably in the form of a "special building" permit that grants him or her sizeable kickbacks from construction. A bank too can function to funnel ill-gotten gains to the ruler's Swiss bank account, instead of fostering urban development or providing an off-shore tax haven for the tourists. Players should be careful of stealing too much though, as it can be a major drain on the economy, and offensive to the elements of the population not auditioning to be sheep. Like any good machine politician, it is better for the player to steal, but not too much, and put something back into the country. Corruption should not amount to wholesale, consistent looting of the economy. Throughout, Tropico is a fun game, with abundant color, atmosphere, and a highly-developed sense of humor. Under all of that is also noticeable simulation value. No, no one is going to mistake for an academically-rigorous simulation of Third World economics and politics. Yet one does experience many of the same problems as a Caribbean or Central American ruler, especially a dictator. There is a need to grow the economy, and choices to be made on how to do it. There are also temptations, including that to steal from the public purse. The player must keep the people relatively happy and respectful, even if he or she wants to be a despot, which is realist. Even the worst dictator works to keep the people quiescent if not ecstatic, content if nothing else, do to little more than lowered expectations. A gamer has to deal with random events too, ones that a real-world counterpart would recognize. Tropical storms and hurricanes are devastating events, possibly wrecking everything not made of masonry and setting the country back to square one. A superpower sponsor might send relief assistance, yet is seldom enough to make up for the destruction, and besides, it is unlikely that there will be enough construction workers to rebuild on a timely basis. Shipping strikes too can cripple Tropico's ability to export goods or bring in needed immigrants. Shipping strikes, like bad play, usually results in an austerity measures, courtesy of the international lending community. In these cases, debt by itself has already prevented the player from undertaking any new construction. An austerity mandate then holds down wages, which is not conducive to contentment among the body politic. For all of this, the primary goal of Tropico is not simulation. It is supposed to be fun, first and foremost. Tropico succeeds on both levels. As a simulation, it is surprisingly good. As an enjoyable game, it is little short of brilliant.

|